CHAOS IN THE COCKPIT- AIR FRANCE FLIGHT 447

- Anay Baid

- Jul 12, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Nov 4, 2021

Aeroplanes are modern and sophisticated instruments; they are a wild mix of complex electrical circuits and seemingly endless knobs and switches, that perform the wonder of transporting us over very long distances in an “instant”. With great advancements in modern technology, tracking them becomes an extremely routine task.

The very idea of a modern aircraft going missing in the 21st Century is bewildering and unthinkable. But this is exactly what happened to an Airbus A330, flying in the middle of the Atlantic in the middle of the night.

For more than two years, the disappearance of Air France Flight 447 over the mid-Atlantic in the early hours of June 1, 2009, remained one of aviation's greatest mysteries. How could a technologically state-of-the-art airliner simply vanish?

It was a long wait for bereaved families and relatives to have a chance to find out what went wrong. Miraculously, the CVR and the FDR were retrieved from the bottom of the Atlantic.

These incredible tapes don’t only reveal what caused the crash, but also raise an alarming and disturbing question, just how safe was flying today?

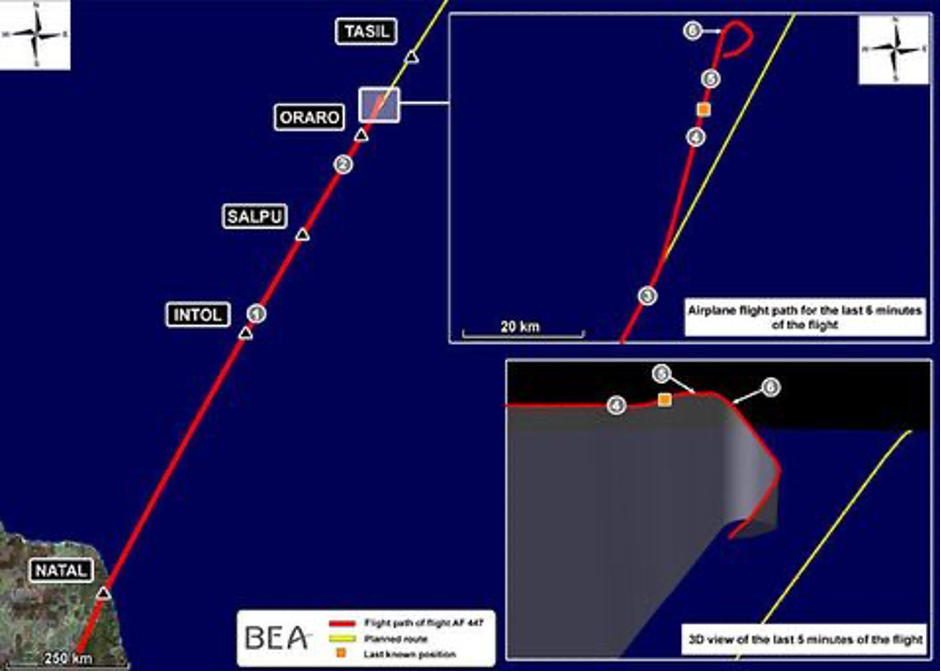

AF447 passed into clouds associated with a large system of thunderstorms, its speed sensors became iced over, and the autopilot disengaged. In the ensuing confusion, the pilots lost control of the aeroplane because they reacted incorrectly to the loss of instrumentation and then seemed unable to comprehend the nature of the problems they had caused. Neither weather nor malfunction doomed AF447, nor a complex chain of error, but a simple but persistent mistake on the part of one of the pilots.

Human judgments, of course, are never made in a vacuum. Pilots are part of a complex system that can either increase or reduce the probability that they will make a mistake. After this accident, the million-dollar question is whether training, instrumentation and cockpit procedures can be modified all around the world so that no one will ever make this mistake again—or whether the inclusion of the human element will always entail the possibility of a catastrophic outcome.

After all, the men who crashed AF447 were three highly trained pilots flying for one of the most prestigious fleets in the world. If they could fly a perfectly good plane into the ocean, then what airline could plausibly say, "Our pilots would never do that"?

The conditions in the cockpit were also strange and eerie that night. As the plane passed over the Intertropical Convergence Zone, a sharp chlorine-like smell entered the cockpit which took the first officer Bonin by surprise. Strange electrical phenomena and discharges like St Elmo’s fire were also observed that night. Although these things were quite common while flying over the tropics and storm systems, Bonin was particularly distressed and that caused him to do something no pilot would ever imagine doing.

Perhaps spooked by everything that had unfolded over the past few minutes—the turbulence, the strange electrical phenomena—Bonin reacts irrationally. He pulls back on the side stick to put the aeroplane into a steep climb. This caused the plane to enter a potentially dangerous and unrecoverable stall, but Bonin kept pulling back on his sidestick all the way till the end, not realising the same.

Bonin's irrational behaviour is difficult for professional aviators to understand. "If he's going straight and level and he's got no airspeed, I don't know why he'd pull back," says Chris Nutter, an airline pilot and flight instructor. "The logical thing to do would be to cross-check"—that is, compare the pilot's airspeed indicator with the co-pilot's and with other instrument readings, such as ground speed, altitude, engine settings, and rate of climb. In such a situation, "we go through an iterative assessment and evaluation process," Nutter explains, before engaging in any manipulation of the controls. "Apparently that didn't happen."

Today, the Air France 447 transcripts yield information that may ensure that no airline pilot will ever again make the same mistakes. From now on, every airline pilot will no doubt think immediately of AF447 the instant a stall-warning alarm sounds at cruise altitude. Airlines around the world will change their training programs to enforce habits that might have saved the doomed airliner: paying closer attention to the weather and to what the planes around you are doing; explicitly clarifying who's in charge when two co-pilots are alone in the cockpit; understanding the parameters of alternate law, and practising hand-flying the aeroplane during all phases of flight.

But the crash raises the disturbing possibility that aviation may well long be plagued by a subtler menace, one that ironically springs from the never-ending quest to make flying safer. Over the decades, airliners have been built with increasingly automated flight-control functions. These have the potential to remove a great deal of uncertainty and danger from aviation. But they also remove important information from the attention of the flight crew.

While the aeroplane's avionics track crucial parameters such as location, speed, and heading, human beings can pay attention to something else. But when trouble suddenly springs up and the computer decides that it can no longer cope—on a dark night, perhaps, in turbulence, far from land—humans might find themselves with a very incomplete notion of what's going on. They'll wonder: What instruments are reliable, and which can't be trusted? What's the most pressing threat? What's going on? Unfortunately, the vast majority of pilots will have little experience in finding the answers.

Comments